Give it to me straight Doc, I can take it..

You have seen the scene repeated in a zillion Hollywood movies. The hero has just been told he has cancer. Somber music plays in the background. The wise doctor looks worried and the beautiful young nurse assisting the doctor looks like she is about to cry. The hero looks up as the camera goes in for a close-up, his eyes bleak but no tremor in his voice. He delivers the heart wrenching line with appropriate pathos .. “Give it to me straight Doc. I can take it. How long do I have?”. Pregnant pause as the audience holds its breath and a lone violin weeps gently in the background – then the doctor gives his verdict: “A few weeks, months at most”. There is not a dry eye in the whole theater, no matter how many times we have heard this corny dialogue before.

You have seen the scene repeated in a zillion Hollywood movies. The hero has just been told he has cancer. Somber music plays in the background. The wise doctor looks worried and the beautiful young nurse assisting the doctor looks like she is about to cry. The hero looks up as the camera goes in for a close-up, his eyes bleak but no tremor in his voice. He delivers the heart wrenching line with appropriate pathos .. “Give it to me straight Doc. I can take it. How long do I have?”. Pregnant pause as the audience holds its breath and a lone violin weeps gently in the background – then the doctor gives his verdict: “A few weeks, months at most”. There is not a dry eye in the whole theater, no matter how many times we have heard this corny dialogue before.

That is so not going to happen to CLL patients.

Frankly I do not know of any examination rooms where they play weepy violin music, the doctor and nurse rarely fill the needs of Hollywood central casting, nurses are generally not inclined to cry every time they hear a cancer diagnosis. You would be lucky if you got your doctor’s undivided attention for the full fifteen minutes of your consultation window. Given that CLL is supposed to be the “good” cancer, it is much more likely that instead of corny pathos and empathy you will get flip condescension and told not to worry your pretty little head about it, go home and not bother the nice doctor.

If you are like many patients, you have probably felt a twinge or two of feeling sorry for yourself since your CLL diagnosis. Here you are, dealing with the “big C” and after the first week or so, the universe does not seem to be paying much attention. You look about the same, you are not wasting away, hair not falling out in tufts, you are not even going to have therapy for the foreseeable future. Friends and family wander away – sort of bemused. And you are left alone holding the bag, as it were. Not quite alone, because we are here for you.

What can newly diagnosed CLL patients expect?

How long do early stage CLL patients have to live? What can they expect, by way of quality of life? How soon will they have to start therapy? Here is the abstract of a very recent paper that sifts through a very large database of patient histories to come up with some guide posts. I will do my best to review the highlights, but really, you have to read the full text version of the paper to get all the juicy details. Send me a personal email and I will help you locate the paper. This is article is a keeper for your personal files. I recommend it.

Br J Haematol. 2011 Dec 15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08974.x. [Epub ahead of print]

Defining the prognosis of early stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients.

Pepper C, Majid A, Lin TT, Hewamana S, Pratt G, Walewska R, Gesk S, Siebert R, Wagner S, Kennedy B, Miall F, Davis ZA, Tracy I, Gardiner AC, Brennan P, Hills RK, Dyer MJ, Oscier D, Fegan C.

School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff Medical Research Council (MRC) Toxicology Unit, University of Leicester, Leicester Institute of Cancer Research, Belmont, Sutton, Surrey CRUK Institute for Cancer Studies, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, UK Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital, Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Kiel, Germany Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, UK.

Approximately 70% of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients present with early stage disease, therefore defining which patients will progress and require treatment is a major clinical challenge. Here, we present the largest study of prognostic markers ever carried out in Binet stage A patients (n = 1154) with a median follow-up of 8 years. We assessed the prognostic impact of lymphocyte doubling time (LDT), immunoglobulin gene (IGHV) mutation status, CD38 expression, ZAP-70 expression and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) cytogenetics with regards to time to first treatment (TTFT) and overall survival (OS). Univariate analysis revealed LDT as the most prognostic parameter for TTFT, with IGHV mutation status most prognostic for OS. CD38 expression, ZAP-70 expression and FISH were also prognostic variables; combinations of these markers increased prognostic power in concordant cases. Multivariate analysis revealed that only LDT, IGHV mutation status, CD38 and age at diagnosis were independent prognostic variables for TTFT and OS. Therefore, IGHV mutation status and CD38 expression have independent prognostic value in early stage CLL and should be performed as part of the routine diagnostic workup. ZAP-70 expression and FISH were not independent prognostic markers in early stage disease and can be omitted at diagnosis but FISH analysis should be undertaken at disease progression to direct treatment strategy.

PMID: 22171799

The statistics derived in this study are with reference to early stage patients – Binet Stage A is the equivalent of Rai Stages 0 and 1. The cohort size is very large at 1,154 patients and therefore the conclusions drawn from this study are likely to be robust. (In the editorial section I will have more to say about statistics derived from large groups of patients, and how they apply to a single patient).

As the abstract points out, the purpose of this study is to assess the value of prognostic indicators in predicting two important outcomes of crucial interest to us chickens. First, how long will it be before “Watch & Wait” ends and therapy has to begin? Because, much though we all like to gripe about the Chinese torture of W&W, believe me it beats the alternative by a mile. This period, between initial diagnosis and the time when therapy must be undertaken, is called “TTFT” (Time To First Treatment). The second issue that is even of greater interest speaks to the Humphrey Bogart scenario above, how long are we going to live? The acronym for this is “OS” (Overall Survival).

Who were these patients?

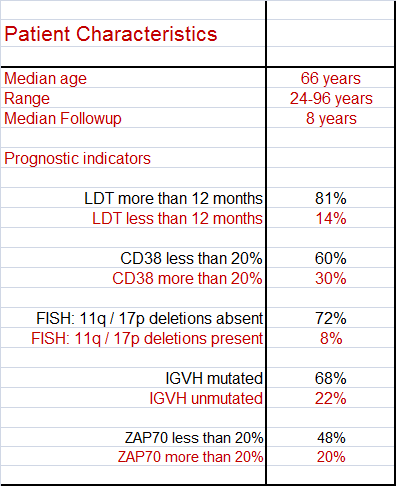

The inclusion criteria for participating in this study is that the patient has to have clinically documented CLL and be in Binet Stage A. Here is a short list of the patient characteristics. Notice the age range, all the way from 24 to 96 years! 24 is way too young to have this nasty disease, and I take my hat off to the brave 96 year old still game enough to participate in the study. Not all the patients had all the prognostic tests done, and that is why the numbers don’t add up to 100% in each category. I have highlighted the good prognostics in black, for your convenience.

Which Prognostic Indicators?

Over the last ten years a bunch of different tests and indicators have been suggested for defining prognosis. I am glad to see the researchers stuck with the tried and true, the prognostic indicators that are rapidly becoming the standard set.

- Patient’s age

- Lymphocyte doubling time (LDT)

- IgVH gene mutation status (IGHV)

- CD38

- ZAP70

- FISH

We have discussed each of these in some detail in earlier articles but if you want a quick refresher course, I recommend an article based on one of our recent workshops: “Prognostic indicators: who, when, what and why”. Most (but not all) of the participants in this study had these prognostic indicators tested and recorded at the time of diagnosis.

Results – Highlights

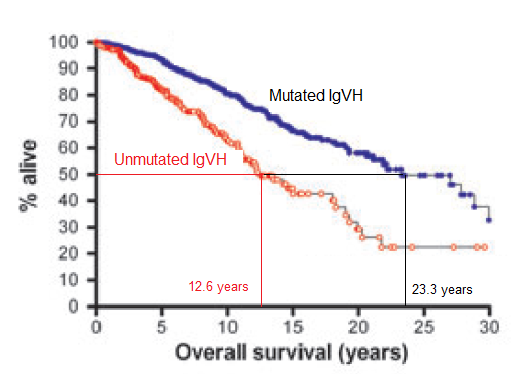

Given below are graphs showing how the time to first treatment (TTFT) and overall survival (OS) changed between patients who had mutated and unmutated IgVH.

The dark blue curve shows how many of the patients with (good) mutated IgVH stayed untreated as the years went by. As you can see, even as far out as 25 years and more, fully half of them had not needed therapy. For these guys, CLL is truly the “good” cancer to have. Not so for the folks with (bad) unmutated IgVH. Half of these guys had to have therapy by 4.6 years. Quite a difference, you would agree.

The next graph looks at the crucial question of “How long do I have?” – namely, overall survival. Once again the dark blue curve is for the lucky mutated IgVH guys and the red curve is for not so fortunate unmutated IgVH. Drawing the horizontal line from the 50% mark, you can see that half of the mutated IgVH guys are still trundling along at 23.3 years, where as this milestone was reached much earlier in the unmutated IgVH folks, at only 12.6 years.

If you also take patient’s age into consideration, this difference between mutated and unmutated IgVH can make all the difference between dying with CLL versus dying because of CLL. For a typical 65 year old CLL patient with mutated IgVH as prognostic indicator, a 50% chance of living beyond 88 years sounds pretty good! But the scenario is not so rosy for a 40 year old patient with unmutated IgVH, looking at roughly even odds of not making it past 53 years. Prognostics are important in how we think of overall survival, but so is the age of the patient. Please remember that.

The authors have similar time to first treatment and overall survival graphs for the other prognostic indicators (CD38, ZAP70, FISH cytogenetics). They also have differential projections for people whose prognostic indicators do not quite match up, where there is a discordance. But rather than reproducing all those graphs here in my review, I strongly urge you to read the original paper for yourself. As I said, it is one of those must keep articles. Rather than just reproducing all the other graphs, I would like to highlight some of the interesting conclusions reached by the researchers in this valuable study.

Study Conclusions

This study is important not just because it looks at a large cohort, done at very prestigeous institutions and reports the results in great detail, but also because the authors looked at the results and came up with some interesting and important observations. Here are some of them.

- While the Rai and Binet staging systems have been very useful in classifying patients, they both fail to identify which of the early stage patients (roughly two thirds of them) will have progressive disease requiring therapy at some point – and which one third are going to “smolder” on for the rest of their natural lives.

- Taken individually all of the modern prognostic indicators studied (IgVH gene mutation status, CD38, ZAP70, high risk FISH abnormalities) influenced time to first treatment.

- LDT (lymphocyte doubling time) was the single most important prognostic indicator for TTFT. (Figures, this is sort of like the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Patients with short doubling time have demonstrated an aggressive disease, for crying out loud. This is a bit like predicting the weather by looking out the window and ‘predicting’ it is indeed raining).

- When combined together, only this set of four prognostic indicators had the power to predict time to first treatment: LDT, IGVH, CD38 and the patient’s age.

- The researchers wondered whether the strong showing of LDT in predicting time to first treatment has something to do with doctors treating the numbers, getting spooked by high white blood counts even if the patient did not really need therapy right away. Interesting indeed.

- The researchers noted a significant trend for younger patients to receive therapy sooner than otherwise – perhaps once again reflecting physicians’ bias towards treating younger patients more aggressively, while taking a more laid back approach to treating elderly patients.

- This last point is something to think about, if you are in the younger crowd. “Given the increasingly recognized association of CLL chemotherapy with development of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome / acute myeloid leukemia (8-10% of fludarabine combinations treated patients), this observation is very important and worthy of further study”. No kidding.

- Patients with 17p deletion (FISH abnormality) are widely accepted to have poor prognosis. But this study shows that only 53% of early stage patients with 17p deletion needed treatment over a 3 year period. Of note, patients with 17p deletion but mutated IgVH usually had stable disease. Looks like the ‘good’ mutated IgVH takes some of the sting out of the 17p deletion.

- Only 5-7% of newly diagnosed and untreated patients have 17p deletion, and these guys may not have such a bleak future. The situation is very different when patients acquire 17p deletion as clonal evolution during the course of their disease.

- The researchers recommend that once disease progression happens, FISH analysis is necessary in order to develop appropriate treatment strategy. Presence of 17p deletion, for example, changes the ballgame and mandates different therapy options.

- Bottom line, using patient’s age, LTD, CD38 and IgVH mutation status for predicting time to first treatment, and adding FISH analysis when it is time to treat, the researchers believe will be sufficient to identify the two thirds of early stage patients who will progress and need intervention.

Editorial

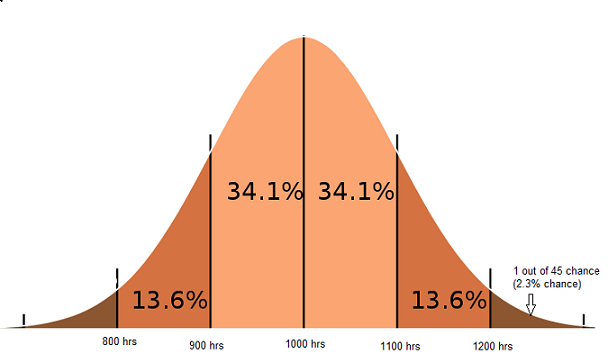

Allow me to give you a simple example of how statistics works, and something called a normal distribution. I promise I will make it clear why and how this applies to cancer patients like you.

You are out shopping for light bulbs. Obviously, you want a brand that has a reputation for lasting a long time without burning out. The manufacturer provides the following information about his light bulbs. He says his light bulbs have a mean life of 1000 hours and a standard deviation of 100 hours. Does this mean all the light bulbs made by the company will last exactly 1000 hours? No, it does not. It means that exactly half the light bulbs will last more than 1000 hours and the other half will last less than 1000 hours. That is precisely what a “mean value” implies. The majority of their light bulbs (68.2% of them) will last somewhere between 900 hours and 1100 hours.

Now, what are the chances that you get lucky and the particular light bulb you pick up lasts more than 1,200 hours? If you do the math using the standard deviation of 100 hours he quoted, it turns out you have a 1 in 45 chance (2.3%) of getting such a super bulb. But remember, there is an equally slim chance (1 in 45) that the bulb you got is a dud and lasts less than 800 hours before giving up the ghost.

So. The point to remember is this. While the vast bulk of light bulbs will last somewhere close to the 1,000 hour mark (the mean of this data set), there are always going to outliers. A few bulbs will last a lot longer than 1,000 hours, and an equally small number of bulbs will die a lot sooner than 1,000 hours. The further you get away from the mean value of 1000 hours, the smaller the chances that you will get such a light bulb, either that extremely good or extremely bad.

Now, lets talk about what all this has to do with CLL patients.

Let us say you fall into a particularly bad prognostic group and the mean overall survival for this group of unlucky folks is quoted to be 5 years. That means in a sufficiently large group of such patients, half of the group would be gone by 5 years, half would survive past 5 years. And here you are, 4 years into this 5 year mean overall survival mark. That sucks!! What to make of it?

If you are not familiar with statistics, you might take that to mean you have one year left to live. You may decide to quit your job, sell your house, say goodbye to heartless family and friends and head out to see the Taj Mahal or the pyramids, buy that red sports car you always wanted – whatever happens to be on the short form of your “Bucket list”. But beware. You may well find that you live past the one year deadline, run out of money and have to slink back home – sans job, money, family or friends. Of course, it is equally likely that you are an outlier on the other (ugly) side of the mean value, and you kick the bucket sooner than the one year you thought you had.

Same sort of logic holds for patients with the best of all prognostic indicators, where the group’s mean overall survival is, say, 25 years. You would not be too far off the mark to look at that statistic and thank your lucky stars. With reasonable safety you can continue to procrastinate getting your affairs in order, writing out your will and last testament or mailing off the checks to your favorite causes (ahem). However, it is important to remember that this good statistic of overall survival does not guarantee that you as an individual will indeed live for another 25 years. Anything can happen. You could get hit by a bus crossing the street. You could develop a second cancer, a nothing squamous cell carcinoma on your balding scalp that decided to get aggressive. Lots of things can go bump in the night.

Which of these scenarios is the right answer? Should you expect to do better than the mean value quoted for your risk group, or worry that you may not do as well as the mean? That depends on your personality, your individual circumstances. Are you an optimist, a glass half full type of guy who expects to win the lottery every time you buy a ticket? Or are you the kind that worries lightning may strike you as you head out into a light spring time drizzle?

There are also more concrete circumstances having nothing to do with optimism or pessimism. Do you have good medical insurance? Do you have a good support system to help take care of you, give you something to live for? Are you otherwise in good health? Do you come from a long line of family that lived well into their eighties? Do you take care of yourself or do you believe in burning the candle both ends?

You see what I mean? Statistical averages based on large groups of patients just give you the odds – what are the most likely outcomes, if everything else is exactly the same. But nothing is ever exactly the same; so while it is important to know the odds stacked in your favor or against you, it is also important to remember your own mileage may vary. That is perhaps the single most important take away lesson from statistics. You are an individual, and group statistics cannot exactly predict what will happen to you. You can influence the odds, either in your favor or against yourself, by the decisions you take. Not always, since Lady Luck is notoriously fickle. But enough of the time that it is worth the effort. You agree?

30 comments on "“Doc, How Long Do I Have?”"

Having been told- without sufficient evidence- that I had MM, then told I had SLL(4) with 10 year survival as the statistical average, and 3 years later that I had MBL with likely ‘too few cells’ to test for IgVH I am angry about the emotional roller coaster. Of course, one may not be angry at such good news given the difficult course faced by others so I prefer to imagine that I never heard any of this and life will take the same course regardless. Obviously, the fault is with diagnosis more than prognosis but if the first step is wrong, the error simply compounds.

I must add that Dr. Hamblin offered guidance through this muddle even while going through his own significant physical distress. May his support be returned to him now a hundredfold.

qb:

I second that sentiment regarding Terry with a full heart. Terry Hamblin has been a good friend to me and my husband. He was the only one of the experts who stepped up to the plate and treated PC with ofatumumab – when it was still an experimental drug and no one else wanted to be bothered. This website owes much to him as well. Let us hope Terry makes a speedy recovery.

Thank you for summarising (and interpreting) the data for us, Chaya.

I’m 44… it seems to me that now is always a good time to let go of the things you don’t need (unrewarding relationships, the garage/basement/attic/closet clutter, mental baggage/grudges, etc.) and today is the best time to start moving forward, lighter and enlightened. My Grandmother who recently died at 91 (I took care of her to the end) taught me well. Her motto was “get it done”. She was healthy until the last month of her life, but she pressed each of us for decades to get our “papers in order” and to go travel “cause you may not always be able to”.

Being prepared—expecting the unexpected—can help others later (wills, healthcare directives, etc.) and free up our own mind space for getting on with an enriched life. Donating anything and everything you can while YOU can decide the details feels good and most importantly, helps others!

Healthy or not so healthy, if you’re not living life in the way you’d like to now, then when might you?

Thank you, Chaya for the great article. I am 51 and was diagnosed with CLL last summer. I struggled to understand the questions you addressed in this article- ‘Given my prognostic indicators, how long until I will need treatment?’ and ‘How long do I have?’. I asked this question on the CLL forum and received some answers and a lot of ‘No one knows- everyone is different’. However, your article gives me a much more meaningful and concrete answer.

I want to thank you for this site and the fantastic information you make available to us. I don’t know how I would have gotten through my diagnosis without this site to help me understand my condition. You are truly an angel and I am grateful for what you have created here.

Aaron,

I am sorry you are dealing with this at 44- I sometimes feel bad that I am 51. I second your sentiment of living life the way you’d like to! CLL has helped me see my life with a new clarity and live more consistently with my values. In this respect CLL has been a gift.

Chaya,

You must have read my mind. I was diagnosed a year ago at 50. My older brother also has CLL and had a stem cell transplant 1 year ago (doing well I might add). But I have fairly young children (both under 11). I was a late bloomer to parenthood but not to CLL. I am trying to decide to move closer to family in the Boston area but I also want them to have plenty of time to be seattled somewhere with all the supports they need in case they must face a life without me. I do the math in my head all the time …hmm ten years ,, my youngest will be 17. As an epidemiologist I know that statistics are helpful but in know way are a crystal ball. I do not know my IgHV mutation status but I am going back to NIH in March and I think they may do the test then.

Once again, thank you for a great article. The one question I have is…how do you know if the pt. has mutated or unmutated IgVH?

Tommy Sidelko:

Many of the leading commercial testing labs now offer the IgVH gene mutation test. Your doctor has to prescribe it – it is not cheap and you need to make sure your insurance covers it.

Thanks again Chaya, as always you do the translations with clear understanding, making it that way for a simple layman too.

I will ask for the full article, or the link for that. Keep well and carry on finding and reporting on articles/trials and new developments. You are a star.

Thank you Chaya,

Your updates are always very informative.

Monique

As I look at these and other charts I try and overlay in my mind a chart showing how “treatments” for CLL have and are developing- be they “cures” or methods to create a stable, chronic condition.

Has the course of the disease for us already been changed altering the curves in this study?

Only time will tell….

Aaron McQ,

Don’t feel lonely I too was diagnosed at age 44, I am now 52 wondering how I got chosen to carry this at a relatively young age. I try to keep working and pushing forward. After 8 years I get my CBC every quarter, had my Dr. run all of the test’s Chaya mentioned above early to create a baseline going forward and to ensure there was nothing outstanding needing immediate attention.

thanks Chaya for you diligence and giving us the tools to at least try to piece this erratic condition.

EAB

I was diagnosed at 51 when the doctors were examining my lymph nodes to see if my breast cancer had spread

to them. It had not. It was first diagnosed as lymphoma since my blood counts were all in normal range. When I

developed symptoms of anemia I went to a CLL specialist who did all of the tests mentioned. I was unmutated.

After 14 years of W & W I had three rounds of FCR. A bone marrow test was done and no disease was found.

My counts are all in the normal range, and it will soon be three years since I had FCR. I continue to see the CLL

specialist every 3-4 months.

Thank you Chaya for another great article!

I’m 53, diagnosed 6 years ago and my hematologist wants to talk treatment at the next appointment because my platelets and hemaglobin are dropping (I feel well, not anemic or out of breath, only a few small lymph nodes and I don’t know if the spleen is swollen – no discomfort or lessening of appetite, etc).

6 years ago I wanted to know how long before treatment and overall survival stats. My hematologist was not sympathetic, asked me what difference would it make knowing. Some of us are comforted by having an idea, others are not. And I think it helps some of our family members too. My elderly parents moved 2500km – I later found out it was to be close to me, just in case I was going to die any day soon. :-(

6 years ago I was told testing for prognostic factors was a waste of time and was expensive. I am keen to have FISH done now – should I have push for IVGH too? I need to do a lot more reading to feel confident I know what I am talking about at my next appointment. It’s not easy – Chaya does a brilliant job of interpreting and bringing this information to us – it really does help. THANK YOU Chaya!

anaturallearner,

I think I’d look for a second opinion, my Doc is the total

opposite from yours. I did all the tests very early after my

diagnosis.

Chaya, thank you for this current article. I would very much appreciate seeing the full material that you recommended reading, so please send on — I will send a separate email as you requested.

I totally related to your paragraph, “Given that CLL is supposed to be the “good” cancer, it is much more likely that instead of corny pathos and empathy you will get flip condescension and told not to worry your pretty little head about it, go home and not bother the nice doctor.”

This is an exact description of my doctor. Flip condescension, outright rudeness and anger are what I get when I ask a simple question. For example, although still within normal range, my platelets had dropped enough to give me concern but when I asked about this he only got angry and in fact, the outer office staff could hear his raised voice. He actually said he wished he “had been a doctor in the 1940s and 50s, when people had reverence for their doctors.

He is so dismissive, it made me wonder about his other patients and I realized how important it is to become an advocate and start a local support group, who must have similar questions. When I gave him permission to share my name with other WW patients in my region, he said, “Absolutely Not!”

Fortunately, I finally have found someone who is very in tune with autoimmune disease (she studied at Johns Hopkins) and thoroughly explains blood work to her patients.

Yes, as you wrote, “Here you are dealing with the “big C” and after the first week or so, the universe does not seem to be paying much attention….And you are left alone holding the bag, as it were.”

Everything you say is so on target, you are an emotional lifesaver when you write, “Not quite alone, because we are here for you.”

I don’t quite know how to start a group in my area because I don’t know how to get a group together. Is there any way of my finding people who would be interested in meeting in the Northern New Jersey metropolitan area. If so, please tell me how to go about this. Anyone reading this email is welcome to write to me and perhaps we can get started.

With best regards to you and all my fellow CLL-ers.

I was diagnosed in 2011 (53 years old) after having gone to see my GP with night sweats in 2006. He laughed himself silly and wondered why my dear Mother had taught me nothing about the ‘change of life’! I found a new GP and voila…..CLL.

I am fortunate to have a really good haematologist in South Africa and after the first cycle was disease free for all intent and purpose:) Now in cycle 4.

As a registered nurse I know nothing when it comes to myself! So at my next visit I will be asking about the prognostic factors and my possible survival? Generally I make a list of questions during the 4 weeks between treatments (FCR)and present this to my physician, he then writes the answers for me to look at when I am not whoozy from the chemo premed!

Thank you for the information! I had been looking on medical websites and then found this website only this week!

Once my treatment is completed I also plan to start a general cancer support group in my area as I believe there has to be a purpose for this diagnosis!? :)

Good luck to all…. and hang in there:)

Mary

I was diagnosed in 1995 (33 years old), it is now 2012 (soon to be 50 years old) and I am only NOW seeing changes in my CLL. I have swollen lympth nodes in several areas, The lympocytes have doubled twice in two months. My spleen is sore and swollen. I also was recently diagnosed with Rhuematoid Arthritis which seems to come hand and hand with SOME CLL patients. I have fevers in the day as well as the night. Do not know if my incompetent doctor is going to treat the CLL yet or not. If I were seeing my first oncologist from 1995 he would of started already. This other doctor I’ve had for four years seems to think it is okay to ignore obvious signs of progression. I also have PMR, GCA and bi-polar II disorder. I know these other conditions are related. I’ve had one really bad staph infection of the breast in 2007. I had a lung infection that lasted six months last winter and thought I was going to die. The infections are getting worse and worse and very hard to control. The arthritic pain is really horrible along with the constant swelling in my neck, armpits, under my ribs and arms as well as legs. I do believe my CLL has jumped from smouldering to stage B.

Snaggler

I still dont get age as a predictor, of course if you live 25 yrs from age 30 you will die sooner than if you live 25 yrs from age 50, but if you are dxed at 30 are you more likely to live a shorter time than 25 yrs. (same question for ttft)

Ambrose

last post I should have said “you will die younger” instead of “you will die sooner”

How sadly appropriate to have this topic at the center of discussion as we read of Dr. Terry Hamblin’s passing from his family’s post on his blog:

“It is with great sadness that we announce that Terry peacefully passed away shortly before 1.00 AM on Sunday 8th January 2012.”

His kindness and compassion for all who turned to him in need will be remembered always.

I am sorry to hear of Dr. Terry Hamblin my condolences to his family and friends.

Obviously Ambrose it is better to get CLL as an old person then someone in the prime of their life. Despite disease though a person should not stop living. I got pregnant at 40 and gave birth to a healthy son at age 41 and would do it all over again. There are no guarantees in life and nobody knows when their life will end. Cancer is a nasty reality that humans have been dealing with for a very long time. I have taken good care of myself, eat right and do not smoke or drink alcohol. Sometimes it doesn’t matter if you do everything according to the so called specialists, you still get dealt the nasty genes or the nasty card of cancer. I think CLL is so unpredictable and so many variants that it is very hard to give a life expectancy to a patient. I was told 10-15 years. That was 17 years ago. I’ve heard 25 years from another doctor, we shall see. Best of luck to you Ambrose and everyone else here who has to deal with this nasty bastard CLL.

Snaggler <- never giving up!!!

Ambrose:

As we age, there is increased wear and tear on our bodies. Older patients as a rule have poorer immune function to begin with, reduced hematopoiesis (reduced ability to make new blood cells, especially red blood cells). Age related anemia is quite common. Therefore, older patients with these and other co-morbidities are closer to the edge even before the CLL takes a toll on the health of their bone marrow, on their stem cell reserves, and their blood counts. This influences the time to first treatment.

As for overall survival, again age plays a role. Older patients are less able to handle the toxicity implicit in more chemotherapy regimens. This is why aggressive combinations such as FCR are contra-indicated in elderly patients. Co-morbidities such as diabetes, cardiac disease, impaired kidney and liver function etc are all more prevalent in older patients and these play a big role in choice of therapy, as well as restrictions on the dosages that can be used safely.

Please remember the points I made with regard to statistics based on groups of patients and the variability in individual patients. I don’t want every one of you out there who is getting on in years but are in excellent shape to jump on me for giving this general picture of older patients.

Chaya: Thanks for your explaination on the Age factor. This makes sense. I had misunderstood it to mean that younger people had more aggresive CLL.

I am very sorry to hear of Terry Hamblin’s death. He was a good friend to all of us.

Annette

It is with great sadness that I heard Dr.Terry Hamblin passed away on Sunday afternoon.

His kindness and generosity to many CLL patients will be long remembered.

Chaya, I am with you in this sad time. You lost a good friend.

This is my first comment at this site, so a brief intro of me as a CLL pt.

Diagnosed officially 2/27/2001@ age 60. 1 palpable (golf-ball) arm pit node that seems to lessen in size at times) spleen at least palpable at most visits and sometimes liver, also. Will get results 1/18/12 of an MRI w/ dyes that was done because of wt. loss and abdominal pain, mostly on left side at spleen and below level.

Thank you, Chaya, for your excellent presentations. I have been following the site since 2009. I have some questions about testing possibilities but they may not be appropriate here.

Sorry for the loss of your friend.

Again, thank you for this site.

Chaya,

I have almost completed this prognostic indicator time TTFT informal check list: I know, I know, {my labeling-not yours}, :}.

Age 51, zap 70+, CD 38 +, IGVH un-mutated, LDT 9 mo, the one I am lacking is the FISH studies, I had one done when I was dx 03/10, and another at NIH in 04/11 when I joined the Natural history study. No deletions. I am having another one done in May. The team at NIH are not sure why I do not have one of the common deletion markers, (yet) but speculate I may have a deletion at a lower level. I did have a CT scan thursday, that showed an enlarged spleen, and enlarged abdominal nodes.

even with these prognostic indicators I am not sure when I will need treatment, but it seems to me I must first find out which “deletion”/”abnormality is driving the bus, so as to find the best course for treatment if/when…

Thanks for all you do….look forward to your next workshop

js.

my husband was diagnosed with CLL six years ago……….since that time he has undergone many transfusions, 4 complete rounds of chemotherapy, some very very strong and harmful. The lowest his white counts ever went was 32.2……….he has lost 78 pounds. At this time he is very weak, too weak for successful chemo treatments……..right now his hematacrit is at 32, he doesn’t need another transfusion. His white count goes up from 35 to 50 points every couple of weeks. He is now at 278.3. He is so weak physically he can barely make it to the bathroom on his own, seldom gets out of his chair during the day and without meds he doesn’t sleep well at all. He developed a chronic cough about 2 years ago, it never gets better, he has had pneumonia 4 times in the last 3 years. My question is what can I / We do for his comfort now? He has been eating pretty well, drinks a lot of fluids, and ensure. He will not take any more chemo, even if it is suggested, which it hasn’t been, because he nearly died from the side effects of the last one . We would just like to know what we can do now, for his comfort…….it is so very hard to watch him go downhill every day. He is now 70 yrs old. thank you for any input or suggestions…..

I was dx 4/2012 with cll. I had never heard of it until then.My wbc at that time was 18.2. I go back in 8/2012 for recheck and more blood work. Right now I have swollen lymph nodes in my neck. They are uncomfortable. I don’t really know if I should see my DR. or not. I am going into surgery in a few day tohave my gallblader removed. Should I be concerned about the lymph nodes?

My CLL was found when I was 63 in 2003. Oh, yes! We have the good one. I thought leukemia was a blood disorder – think again, huh? The Dr. left me doubt about chemo in the future & no transplant at my age. Chaya, I found you shortly after this and read it all! YOu saved me many a “sleepless” night to put it mildly.

You know I asked for the FISH, ZAP & IVGH. My doc called the Mayo CLinic to find out how to draw the blood for the FISH. There were no deletions, ZAP 70 was high & IVGH did not come in well. I was the first and now he has everyone of his patients drawn for it as a routine. I’m still doing well and the doc can’t understand this and asked what I eat. “Fruit” and a lot of it – the blood count is still low, thankfully. Perhaps this hint will help someone else.

Thank you Chaya for getting us through some very tough emotional times.

Leave a Comment